Why leave everything you know and love behind, and go on a 2,000 mile trip in a strange country, while in the process you risk being killed by dysentery, cholera, heat, hunger or cold, being eaten by wild animals, drowned, or -best of all- being scalped by Indians?

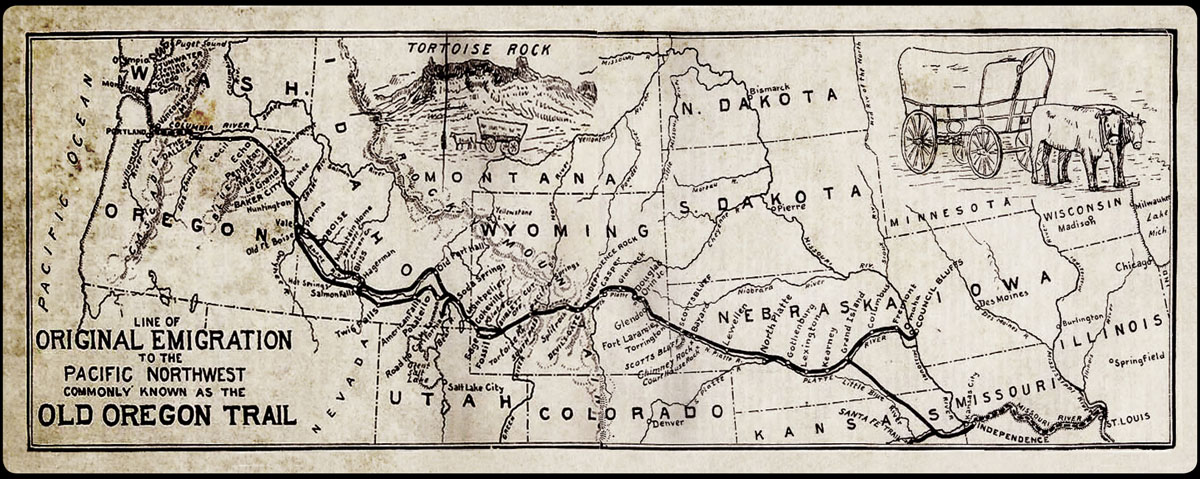

It is very hard to imagine that people living in the US in the second half of the nineteenth century even considered moving all the way to this unknown wilderness. The land between the scarcely populated Pacific coast and the area west of the Missouri river, through which the Oregon Trail would once go, was rugged and mostly unmapped. It went right through the middle of the Great American Desert, for God’s sake! The sparse information that was brought to the more populated east coast consisted of the stories of the traders, trappers and a few overzealous missionaries, the only white men who had ever crossed this vast and empty land.

Still, between about 1840 and 1860, some 300,000 people (about the same amount that today live in Boulder County) undertook this trip to the unknown west. More than 16 per cent of them -about 50,000- went to Oregon, where the majority of them settled down in the fertile Willamette Valley.

So why did they go? In diaries and letters to friends and families back east, reasons often given were a want for economic improvement, better health, running from the law, a broken heart, a strong religious urge (missionary work among the Indians), or just general restlessness and the desire for some good old-fashioned adventure. Some said they heard the fishing was better in Oregon.

Press and politics had a huge influence on the future emigrants. In the eighteenthirties Oregon was just limbo, the home of many Indian tribes, but with huge possibilities, and it was being claimed by both the US and England. A number of American politicians felt that it was important that this ‘new’ land should be settled by American citizens as soon as possible. This would make it easier to claim the territory and place it under the wings of the United States eagle. To make sure that enough people would go to Oregon, politicians used a simple but effective strategy: they made heroes of the people who went. ’The brave men who took “the arts of civilization” into the wilderness’, ‘hardy sons of the frontier’, were just a few of the flattering things future Oregonians read or heard say about themselves. It was a clever way to turn hardship into challenge, suffering into a very patriotic and heroic deed. Something that was destined only for a special kind of person: the American pioneer. And somehow, conveniently, a lot of people fit the profile.