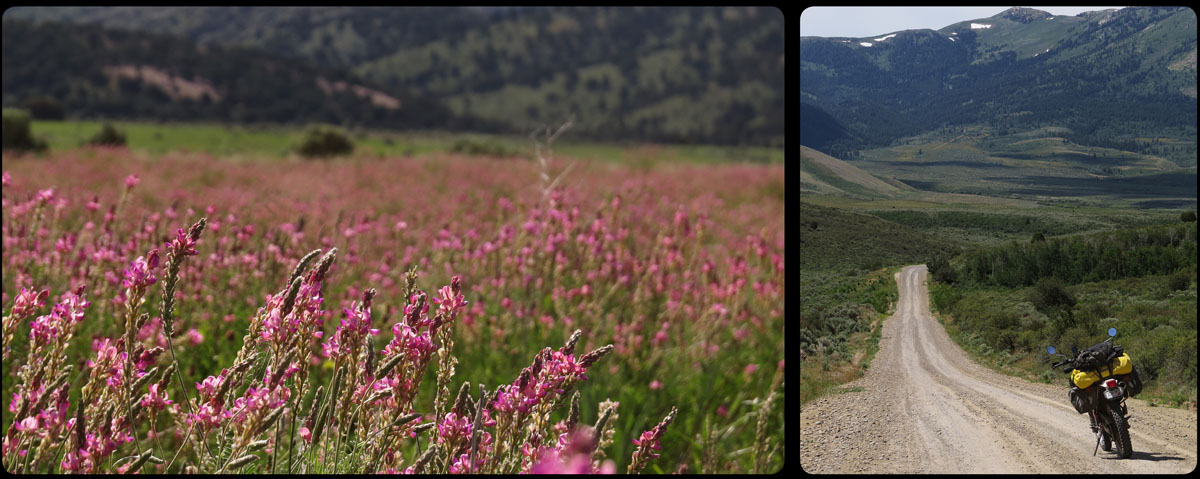

Today I rode through the Fort Hall Indian Reservation, north of Soda Springs, Idaho, where the Oregon Trail used to go. I was unsure if I was allowed to ride here at all. I knew that in some reservations non-residents are not allowed to enter. Yesterday, I tried to gain some information about it at the Ranger Station in Soda Springs, but unfortunately that was closed on Sunday. Subsequently, I bothered several complete strangers about it. They were all very friendly, and they all told me that it should not be a problem. It was enough to convince me to go. Besides, I was wearing my ‘scalp-protector’, and should things really go wrong; I would also have two mirrors on my bike.

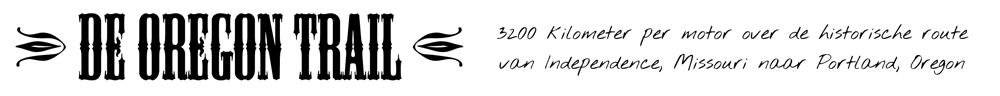

The area north of Soda Springs is very green, thanks to the Pontneuf River that runs through the wide valley. I saw grassland, flowers and numerous birds everywhere. Farmers were busy harvesting the hay, which was pressed into enormous green sugar cubes by an impressive-looking machine. Afterwards they were spat out onto the cropped meadow. Behind this ‘sugar cube-pressing machine’ dozens of gulls were flying, as if they were hovering above a fishing boat on the sea. It was a strange sight to see, on these green meadows of Idaho.

I didn’t see any Indians today, except one in a Fort Hall Indian Reservation car. It was probably some kind of tribal ranger, who keeps an eye on everything because trespassing is not allowed here.

I meant to stop and have a chat, but at that very moment, all my attention was focused on the road that had turned into what seemed to be a river bed covered with fist-sized boulders. As I passed by, the ‘ranger’ raised his hand to greet me (Indian humor?) and I returned his greeting enthusiastically, an impulsive reaction that nearly cost me dearly; the bike started swaying like a fish fresh out of the water. Better keep both hands on the handlebars, just like my mother told me.

Before the emigrants left home, they had heard and read numerous stories about these ‘bloodthirsty’ Indians, stories that were exaggerated further by the press. So imagine the surprise of travelers to Oregon and California when they discovered that the Indians they met were actually very friendly. Often they would trade: emigrants would receive animal skins, moccasins, or meat; in return they would give things like knives, needles, tobacco, blankets or clothes.

Until the eighteen-sixties there were very little skirmishes between white people and Indians. Sometimes cattle of overlanders was stolen or a group of Indians would invite themselves along a wagon train for a few days, something that might cause some irritation among the emigrants, especially since the wide robes the Indians wore could hide a lot of cutlery.

White men, however, would shoot the game the Indians had to live off and the cattle of the overlanders would graze the same grass the buffalo needed as well.

From about 1845 on, the white men would travel west by the thousands, and the Indians started to realize that their way of life was seriously threatened; the buffalo were being exterminated and the many treaties made with the Indian tribes were not respected by the whites. The Indians slowly lost their patience, something that would eventually result in the Indian Wars, when Indians tried to resist the whites on a much larger scale. And if history had turned out just a little different, I would probably have ridden through the Fort Hall Emigrant Reservation today.